John Williams Talks JAWS

Rarely have six basses, eight celli, four trombones and a tuba held more power over listeners. Especially in a movie theater.

John Williams’ score for Jaws ranks as some of the most terrifying music ever written for the cinema (and, according to a 2005 survey by the American Film Institute, among the top 10 most memorable scores in movie history).

The music of Jaws was as responsible as filmmaker Steven Spielberg’s imagery for scaring people out of the water in the summer of 1975. Its sheer intensity and visceral power helped to make the film a global phenomenon; Spielberg compared it to Bernard Herrmann’s equally frightening, indelible music for Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

Jaws will be released for the first time on Blu-Ray Aug. 14, fully restored and digitally remastered as part of Universal’s 100th anniversary celebration. Its 7.1 surround-sound mix is expected to showcase Williams’ Oscar-winning music more spectacularly than in any version to date.

The film was only Spielberg’s second feature film as director, as the composer pointed out in a recent conversation at his studio on the Universal lot. The pair had first worked together on Spielberg’s debut film The Sugarland Express (1974).

“I knew about the novel,” Williams recalled. “I don’t think I read it, but Peter Benchley’s book was very, very popular. I remember seeing the movie in a projection room here at Universal. I was alone; Steven was in Japan at the time.

“I came out of the screening so excited,” Williams said. “I had been working for nearly 25 years in Hollywood but had never had an opportunity to do a film that was absolutely brillliant. I had already conducted Fiddler on the Roof, and I had worked with directors like William Wyler and Robert Altman and others. But Jaws just floored me.”

Williams viewed Spielberg’s thriller about a giant Great White shark terrorizing New England beachgoers as a chance for music to make a major contribution. Not only could he characterize the predatory fish in dark, powerful terms, but, as he remembers telling Spielberg, “I really saw this as a kind of sea chase, something that also had humor, so the orchestra could be swashbuckling at times.”

First to come – and the only music that Williams demonstrated for Spielberg prior to the recording sessions – was the shark motif. He found a signature that not only fit the creature but proved flexible enough to function in as many ways as the shark itself: Sounds from deep in the orchestra (low strings, low brass instruments) that were also rhythmic: “so simple, insistent and driving, that it seems unstoppable, like the attack of the shark,” Williams explained. The music could be loud and fast if he was attacking, soft and slow if he was lurking, but always menacing in tone.

Surprisingly, the director took a bit of convincing. “I played him the simple little E-F-E-F bass line that we all know on the piano,” and Spielberg laughed at first. But, as Williams explained, “I just began playing around with simple motifs that could be distributed in the orchestra, and settled on what I thought was the most powerful thing, which is to say the simplest. Like most ideas, they’re often the most compelling.”

According to Williams, Spielberg’s response was: “Let’s try it.”

Williams spent two months writing more than 50 minutes of music for the film. They recorded in early March 1975 with a 73-piece orchestra. “It was a lot of fun, like a great big playground,” the composer recalled. “We had a really good time, and Steven loved it.”

Loved it so much, in fact, that he decided to get involved. Early in the film, a high-school band is playing a Sousa march during a street parade, and Williams needed to record a terrible-sounding rendition with his orchestra, which included many of the finest musicians in Hollywood. “It’s very difficult to ask these great musicians to play badly,” he pointed out. But Spielberg, who played clarinet in a high-school band, decided to join the orchestra on that one number. And, says Williams, “he added just the right amateur quality to the piece. A few measures still survive in the movie.”

While the shark theme remains the most famous part of the Jaws score, Williams’ entire score is musically diverse. He wrote a delightful promenade (amusingly titled “Tourists on the Menu” on the original soundtrack album) for the Fourth of July crowds at the Amity beach, and an eerie soundscape for Quint (Robert Shaw) relating his horrific experience as a survivor of the sunken USS Indianapolis.

A favorite part for Williams is the “shark cage fugue,” as Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) assembles the underwater apparatus that will enable him to observe the underwater predator up close. Drawing on his classical training, Williams composed a Bach-like piece that both indicated the complexity of the job and the urgency of the moment.

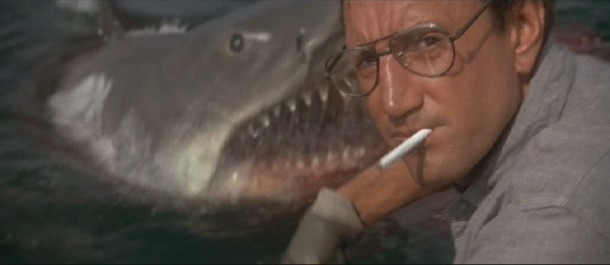

Roy Schider in “Jaws” – “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”

There was a lighthearted hornpipe (a traditional sailor’s dance) heard when the Orca departs the Amity harbor for the open sea, and brass fanfares for the boat chasing the shark at sea. “It suddenly becomes very Korngoldian,” Williams noted, referring to Erich Wolfgang Korngold, the famous Austrian composer who scored so many pirate movies in the 1930s and ’40s; “you expect to see Errol Flynn at the helm of this thing. It gave us a laugh.”

Williams was not in America when Jaws was released on June 20, 1975 and immediately took the moviegoing public by storm. He was in London working on a stage musical. He recalls one of his collaborators entering the theater one day and informing him “that shark thing is all the rage in the States.”

Jaws not only became the highest-grossing film of its time, it propelled John Williams into the front rank of modern film composers. He won his second Academy Award for the score (one of five he has today) as well as a Golden Globe, a Grammy and BAFTA’s Anthony Asquith Award for film music. Together with Star Wars – which Williams would compose two years later for Spielberg’s friend George Lucas – the phenomenally successful music for Jaws brought about a resurgence of interest in the symphonic film score and paved the way for such future Spielberg-Williams masterpieces as E.T., the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) and Schindler’s List (1993).

More than anything, Williams’ music for Jaws helped the director achieve his goal: to scare the wits out of moviegoers. As Spielberg later put it: “I think the score was clearly responsible for half of the success of that movie.”